Back in June of 2011, just as excitement for the newly returned Jets gripped the city, I made my way down to Minneapolis for the 2011 NHL Entry Draft. For local hockey-crazed fans, it was memorable, to say the least. The hockey media were out in full force – those from TSN, Sportsnet, The Hockey News, and virtually every other major hockey media group in North America. (Including Illegal Curve).

TSN Crew: Geno Reda & Darren Dreger (plus Ryan Rishaug off to the left)

The arena was also teaming with agents, each of whom hoped for their most prized prospect(s) to be taken early, so that both player and agent could cash in on the bonus potential that accompanies a high first round selection. Naturally, all the big names from the world of hockey representation were there – J.P Barry and Pat Brisson from CAA, Don Meehan and Pat Morris from Newport, the guys from Octagon (including the controversial Allan Walsh), and scores of others. After the agents, you had the hockey operations people – GM’s and assistants, the amateur scouting staff, player development personnel, etc. – and in some cases, even the owner’s kids, (i.e., the Oilers), or a “face-of-the-franchise” type-player who helps make an important pick. (Also the Oilers).

Taylor Hall was part of the entourage that selected Ryan Nugent-Hopkins 1st overall in 2011

And lastly, and most importantly, you have the young men and their families – most of whom are just 18 years old – who are caught up in the pressure of what has become an international sporting event in itself.

Sidebar – did you know: The first NHL Draft – then called the NHL Amateur Draft – was held in 1963. It wasn’t until 1980 that the draft first became a public event, where mere fans could attend. It wasn’t even televised until 1984. Furthermore, every NHL draft from 1963 until 1984 was held in Montreal! Teams certainly weren’t clamoring for the right to host the event, which, though important, lacked any sort of prestige at the time.

Between watching Mark Chipman formally rename the Jets, and witnessing Kevin Cheveldayoff pass on the ‘consensus’ pick – Sean Couturier – opting for the relatively unknown Mark Scheifele, in front of about 50 shocked and incensed Jets fans who had made the drive down to Minneapolis – the event was unforgettable.

Jets’ 2011, 6th round pick Jason Kasdorf, along with his family. Jason was not only drafted that day, but by his home town team. Five years later, he remains the only Winnipegger to be drafted by the new Jets franchise. He left the organization when he was included in the blockbuster trade in February, 2015, which sent Evander Kane to Buffalo.

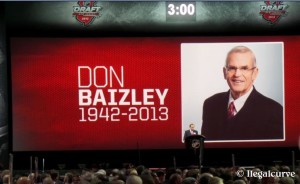

But despite all that excitement, perhaps the most memorable moment of all came in the stands with one of the non-playing legends of the game, the late Don Baizley. A long-time agent for star players like Teemu Selanne, Jari Kurri, Peter Forsberg, and Paul Kariya, Baizley, then 69, was already in declining health from a battle with cancer (which ended 2 years later, in June 2013). To say that Baizley was universally respected throughout the hockey community would be an understatement – many described in terms befitting a saint. He approached his work and his life with great humility, and had a simple, honest, and straightforward approach. He was lauded for being far more than an agent, but also a mentor, and sometimes even a father figure to many of the players that he represented.

I spotted him coming towards me up the stairs, greeted him tentatively, “hi Mr. Baizley”, and thought it wise to mention I was from Winnipeg. As a fellow Winnipegger, he perked up immediately, and I had the tremendous honour of spending 10 minutes with him, basking in his experience. I remember asking him how a player as skilled as Jordan Eberle – who had recently been drafted 22nd overall in 2008 by the Oilers, but who looked like a star in the making – could be passed over by so many teams. In response, he told me a great story about one of his first clients, and my favourite player, Joe Sakic.

Baizley met Sakic when he was just a teenager playing for the Swift Current Broncos. Despite Sakic’s undeniable talent, which saw him rip apart the WHL with 60 goals and 133 points in just his rookie season, scouts and managers had their doubts. Size was never an asset for Joe – even once he filled out, he was just 5’11, 185 lbs, so you can imagine how he looked in his younger days when he was rail thin, weighing at most 165 lbs (soaking wet). But surely, his skating was a strength on draft day? While he certainly become a great skater years later, he didn’t have an especially swift stride as a teenager. Lastly, and perhaps most unsettling for scouts and GM’s was his demeanor. While Sakic’s personality was later described as “quiet” and “humble”, as a 17-year-old, many misinterpreted his shyness for insecurity, and for a lack of intensity. Old timey hockey men even thought he might be ‘soft’ as a result: “Sure, he has great hands, but he’s gonna get crushed by the big boys in the NHL.” The Quebec Nordiques “took a chance” on the skilled, slight, and understated Sakic, drafting him with the 15th pick in the 1987 Draft. In the end, Sakic scored 625 goals, and 1641 points, all with the same franchise. (Although the Nordiques later became the Colorado Avalanche).

In hindsight, it seems ridiculous given all that Sakic went on to accomplish, especially from a leadership perspective – he was named team captain in 1992, won two Stanley cups with the Avalanche, including a Conn Smythe in 1996 as playoff MVP, and was the top player in the 2002 Olympics, leading Canada to their first Olympic Gold in 50 years. His leadership style was lauded – he was a man with “quiet intensity”, who let his work ethic and and on ice play provide an example for others. (Despite this, there were other roadblocks earlier in his career – Baizley also mentioned that even after Sakic had established himself in the NHL – he posted a over 100 points three times before he was 25 – he was left off of Canada Cup squads, supposedly because his legs were “too weak”.)

The Moral of this Story

There are a few implications for drafting that apply as much today as they did in 1987. Firstly, that a player’s physical characteristics often play too prominent a role in selecting – or not selecting – certain players. All else equal, of course you’d prefer that a young prospect have more size, strength, reach, and speed – but anytime you value those physical traits as highly (or even more highly) than you value skill and hockey sense, you’re setting yourself up for failure.

Furthermore – and along the same lines, anytime a dominant player-type emerges that is based on extreme physical characters – i.e., the next Zdeno Chara – a 6’9 shutdown defenceman whose massive shot is also devastating on the powerplay – some scouts and GM’s get greedy, and start looking for a replica. But when you go hunting for bigfoot (literally), and start seeing Chara in some of the d-men that are 6’6+, instead, you often end up with guys like Boris Valabik, Joe Finley, Vladimir Mihalik, Jared Tinordi, and Jamie Oleksiak – most of whom already fizzled out in the NHL, if they made it at all. (Oleksiak and Tinordi are still around, but things aren’t going well). Similarly, if you start looking for your next power forward to pencil into your top-6 – a Milan Lucic type player – instead you may get Hugh Jessiman, Colton Gillies, Kyle Beach, Zach Kassian, or Tom Wilson.

Now that isn’t to say that any or all of these prospects should never have been drafted – only that many of them were a reach at the spot they were selected in. For instance, Joe Finley was selected 27th in 2005, whereas a pretty good NHL defenceman – Matt Niskanen – was taken just one pick later. The same could be said for Mihalik (James Neal was taken 3 picks later), and many others on this list.

Bad picks are unavoidable – even a large percentage of the first rounders will either fail to reach the NHL, or fail to make much of an impact – so maybe the question isn’t “what percentage of picks make the NHL”, but rather, “what percentage of draft picks become impact players”? While it’s great to draft and develop your own players, if a group of scouts puts too much emphasis on size and skating, they may end up with a larger proportion of bottom-6 forwards and bottom-pair defenceman – spots which can easily be filled free agency at a low cost. Conversely, if a team focuses on skill and hockey sense, they may not necessarily end up with more prospects making the league, but they’re more likely to end up with a few high-end offensive players – the type that rarely hit free agency, and are difficult to acquire via trade (as they may cost a king’s ransom).

Part 2 of this series will look at this topic in more depth. For now, quickly scan the recent draft history of two very different organizations:

New Jersey Devils’ Draft History

Detroit Red Wings’ Draft History

Which one is measuring their draft picks primarily on skill?